April 24, 2009: Barry Cauchon

Author Andrew Jampoler

Andrew C. A. Jampoler is a retired US Navy Captain who, amongst his many achievements, served in Vietnam, worked at the Pentagon, commanded a land-based maritime patrol aircraft squadron and a naval air station. He also flew Lockheed P-3 airplanes in search of Soviet submarines during the 1970s and 80s. After retiring from the Navy, he worked in the international aerospace industry and then moved on to become a full-time writer.

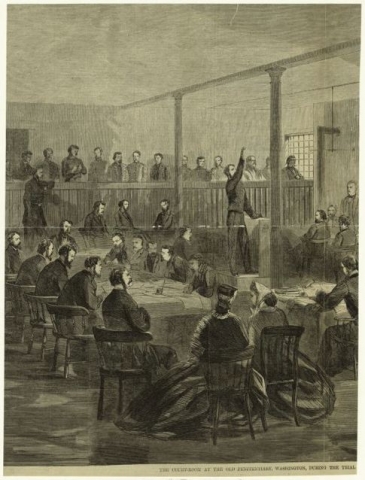

Recently I had the pleasure of speaking with Andy, the author of three books: The Last Lincoln Conspirator: John Surratt’s Flight from the Gallows (2008); Sailors in the Holy Land: The 1848 American Expedition to the Dead Sea and the Search for Sodom and Gomorrah (2005) and the award-winning Adak: The Rescue of Alfa Foxtrot 586 (2003). The latter was voted “Book of the Year” by the US Naval Institute Press in 2003.

Andy is a true storyteller, walking me through each of his three books as well as his current project Horrible Shipwreck (working title) which tells the tale of the wreck of the female convict ship Amphitrite in 1833.

He is a fascinating man with fascinating stories to share. I am very happy to bring you my interview with Andy Jampoler and I hope you enjoy it as much as I did.

——————————————————-

B. It’s nice to speak with you Andy. I wanted to tell you that I’ve enjoyed our emails back and forth this week. Please let me welcome you to A Little Touch of History.

A. Hello Barry. It’s good to be here.

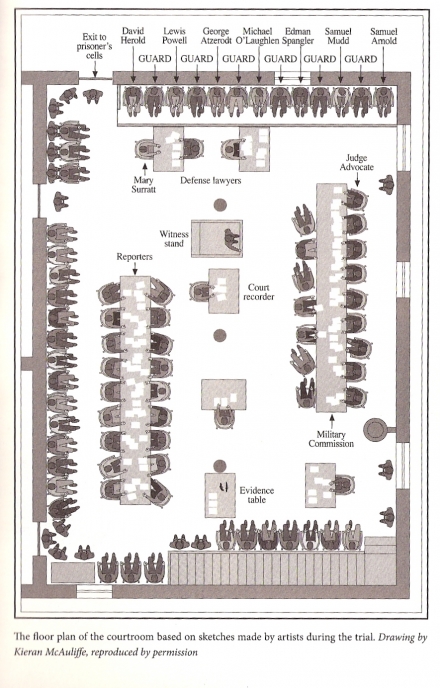

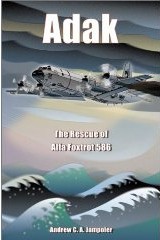

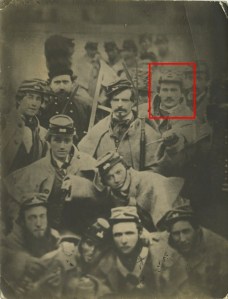

I was really dazzled by your site. It fascinated me. If you get a chance to read “The Last Lincoln Conspirator” you’ll see that one of the Gardner photographs is one of the illustrations in the book. Because they are such high quality, I zoomed in on the gallows. And I remember when I saw those at the Library of Congress I was just horrified by them. So when I saw your study it fascinated me. You’ve gone very far with those extraordinary photographs and I was very interested in what you’ve done.

B. Thank you very much. I appreciate it. It was a labor of love. I was very curious. After you’ve looked at the same photographs for hundreds of times, you want to look beyond the main images. And it was very interesting what I started to find within those pictures. I’m still studying the Rooftop View which I find to be the most intriguing of all the photographs because it has so much to see, especially beyond the prison rooftop overlooking the Washington DC cityscape of 1865.

You can clearly see the incomplete Washington Monument and the Smithsonian Institute. So now I’ve started to get my bearings because I’ve just discovered the US Treasury Building and, if I’m seeing it right, I think I can identify the White House as well. It’s been a lot of fun going through this process.

A. Well if that’s true you will have seen half of the principal buildings in the city of Washington. There weren’t that many and you’ve just mentioned about half of them.

B. The Library of Congress and the National Archives are terrific repositories for photographs, maps, documents and the like. Do you use both of those resources when writing your books?

A. I do…and I draw on them very heavily and they are enormously cooperative. The people at the National Archives are very welcoming and the material they have is extraordinary. If you have to use microfilm that is a little hard on the eyes frankly!

B. (laughing)

A. But they are very helpful. Their resources are stunning. And they, and the Library of Congress, compete to be cooperative. I’ve marveled at how helpful they are systematically.

All they get in exchange for their wonderful help is honorable mention in the front of the book. And what I’ve done in the last two books is… they have a speakers program at both places. In exchange for their cooperation I’ve participated in giving talks at both the National Archives and Library of Congress in compensation for their assistance. It gives me the opportunity to tell people how grateful I am for their help. I think both are great national treasures and it surprises me how helpful they can be.

B. You’ve written three books to date and are currently working on your fourth one right now. How is that going?

A. I’m approaching half way. It’s due at the publisher next summer which is to say, something like 15 months. I’ll be on time. Things are pretty much on schedule. I have a trip this summer to do some research that I cannot do here.

B. What is the subject of this book?

A. The working title is Horrible Shipwreck and it’s the story of a female convict ship in 1833. For the moment, it’s my consuming passion.

In late August, 1833 the convict transport Amphitrite sailed from Woolwich just east of London heading for New South Wales, heading for the convict colony in Australia. I begin the story by explaining the story to American readers the reason there was a convict colony in Australia. It goes back to the American Revolution. Until the Revolution convicted felons from Britain were shipped to the American colonies. As children, we learned that the colonies were full of what were called indentured servants. In fact for the most part these people were felons who were sent to the United States, pardoned as part of the process, but then sold into indentured service by the ship masters who had delivered them here. So it was an ideal solution for the British justice system. They got rid of their felons at no expense. They had no requirement to build a prison system which was something they weren’t interested in doing. There was no requirement even to pay for transportation. Well, when the Revolutionary War started, that outlet closed up. And suddenly Great Britain had no place to send their convicted criminals. And these people were convicted of all sorts of things. Small things, large things…mostly theft and robbery. But there was a desperate moment there in the late 1770’s when people tried to figure out “Well, what are we going to do with this tide of felons that are going to wash over society and overwhelm us if we can’t get rid of them anymore?” There was a great hunt started for a suitable convict colony. A number of efforts were made to find such places, for instance the West African coast and elsewhere. Quite rightly, and quickly, they concluded that that would be nothing but a death sentence. There was no place in West Africa where these people would survive.

B. Okay.

A. Then somebody remembered Cook’s expedition to Australia. And very quickly, without any further research, the decision was made in 1778 to launch the first fleet carrying about 1100 male and female convicts to start a new prison colony in Australia, in New South Wales at the time.

B. Andy, I’ve heard the stories of the criminal beginnings in Australia. At the time that this convict fleet sailed was Australia already colonized?

A. No. This is how it began. The program continued for many decades. Ultimately some 160,000 convicts from England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales were shipped to Australia of which 20% to 25% were women. All along there was the intention that this would become a self-sustaining colony. Once again, Great Britain didn’t want to pay for this. In the case of Australia they had to pay for transportation. They had substantial upfront costs because there was no settled community into which these convicts could be integrated. So it began that way.

B. I see.

A. Well by 1833 they had been sending convicts to Australia for nearly 50 years and there had been no shipwreck. Not until the Amphitrite sails has any vessel been lost, although there have been a number of deaths from disease and other causes. There has been no vessel lost and no substantial loss of life other than some horrific fatalities aboard the second fleet due to maltreatment and things of that sort.

But Amphitrite sails from Woolrich and less than a week later she’s caught in a terrific channel storm along with hundreds of other vessels and is run aground outside the city of Boulogne-sur-Mer, the French channel coast. And in the course of roughly the next ten hours the ship is caught on the sands, she’s run aground deliberately but she’s caught on the sands and beaten to pieces by the storm surge, in plain sight of the city. Several efforts are made to alert the crew to what’s going to happen to them if they stay there and don’t leave the ship. Depending on what source you believe for a variety of reasons, the captain, the crew and his convicts are not permitted to leave and all but three die, all but three drown Saturday night, August 31, 1833. And when Sunday comes, the good citizens of Boulogne, about 6,000 of who are British expatriates, discover to their horror that bodies are washing up on the beach in dozens.

My book is the story of the ship, the shipwreck, the public outcry after the investigation the admiralty conducts, and what happened and why. And of course the fact that it’s women and children who were the largest numbers among the dead I think just kind of makes it more poignant and frankly a more marketable story for an American audience.

B. Absolutely. When you first mentioned it to me, I felt it was a story that will be quite appealing.

A. The early vessels that went to the convict colonies had both men and women aboard. That very quickly turned out to be impossible and unworkable. And consequently early on what happens is that all-female transports become the model. There is some financial advantage. They don’t have to put guards on them. The male transports are carrying security detachments because everybody’s afraid of mutiny. The female transports, the people conclude quite rightly, that there isn’t the threat of the ship being taken over by these women, so they are able to put more convicts aboard any given size vessel. So that continues until 1833 when the first of them, Amphitrite goes down in this horrific, highly public accident. All of this happens in clear sight of the beach front of the city of Boulogne right in front of the principal hotel in the city, which happens to be owned by a Brit.

Anyway, that story is due to the publisher next summer and I think it’s an interesting one.

B. Were there good resources available to you considering it was such a public tragedy?

A. The resources are quite good in some areas and I’m still exploring other areas. All the legal documents that resulted in the convictions of these women at trial are very complete. The court system in England, Ireland and Scotland ran much as it does today, on paper. And all of those papers are available so it’s possible to understand in great detail what these individual women were accused off, what they were convicted of, what they were sentenced to, and where and when. So the records there are quite good. The records about the ship are quite good too. There are several principal characters. The captain of the ship, there are some good records about him. I found his will for example which tells me about his family and his property and one thing or another. The surgeon superintendant aboard, the man who is actually in charge of the convicts, he is turning out to be the most difficult to research. And it’s one reason why I’m going to go to Edinburgh because he was a Scot and I think I’m going to have to press harder on some things there. I have an acquaintance in Scotland doing some research for me but I need more on a Dr. James Forrester and his wife. She was accused of being the reason why no boat was launched from the ship to take people ashore, because it is alleged that she refused to ride with common prostitutes in a boat.

The admiralty investigation was conducted by a Navy Captain named Henry Chads, about whom the documentation is very complete. His investigation is very well documented. And there was a woman on the beach, a Brit, Sarah Taylor Austin who played a very important role in the efforts to save the lives of these people. She’s an enormously colorful figure married to a well known failed British lawyer living in France at the time. And the biographical data on her is both fascinating and very good. And there were two Frenchmen who tried very hard to alert the crew to what was happening and to make sure they understood their danger. But the biographical information on them is adequate.

The newspaper coverage in English language papers and French language papers is very good. And especially the coverage stimulated by a British reporter named John Wilks Jr. who is the guy who essentially stirred up the public excitement by his reporting in the Times of London and in the London Standard. He’s an enormously colorful character. He was living in France because he had been ridden out of England as a result of a whole bunch of stock frauds that he traded.

B. (laughing).

A. And all that is very well documented too. So the answer is…the source material is certainly available to do a good job. And it’s my job to take that source material and do the best job that it’s possible to do.

B. I may have missed it but did the accident occur at night?

A. It occurred in late afternoon. During the course of the afternoon the captain found himself….in aviation you say, kind of “out of altitude and ideas and air speed all at the same time”. He had the same problem. He’s being driven on the French coast by a wind out of the northeast. His ship will not go into the wind such that he cannot get away from shore. So he makes the deliberate decision about mid-afternoon to drive her up onto a sandbar to anchor there. He then assumes that the tide will come in, the storm will abate, it will lift him up and he will be able to continue his voyage. What he doesn’t understand, and what the French fisherman at the port do understand, is that as the tide comes in, it will bring with it all the sand that washes around. And that he will be fixed on that bar as the water rises around him. And that the narrow channel that he’s in, he’s in the Pas de Calais, the Dover Strait, that focuses the wind, it focuses the waves and that essentially once he is on that bar his ship will be beaten apart as the tide comes in. They try to alert him to this. For whatever reason he discounts it and it’s exactly what happens. Over the course of the evening, let’s say between 10:00 pm and 2:00 am, Amphitrite is beaten apart and that is when the bodies start washing in.

B. So the captain initially beached his ship!

A. Yes. Exactly! He deliberately took her ashore and that’s not unheard of in those days.

B. So with was his knowledge base at the time, it was the thing to do?

A. Yeah, well he didn’t have any alternatives. He was being pushed ashore and the question was, was he going to manage it or was he just going to be driven sideways somewhere and broach and rollover and that would be the end of it.

B. I see. But the locals who knew the area knew that that was not the place to do it.

A. Two of them, one in a boat and one, incredibly, swimming, went out to his ship to tell him exactly what was happening. And depending on whose story you believe he rejected the advice, or ignored it or had such confidence in what he was doing that he just figured that he would ride it out.

B. How incredible…

A. In fact what they told him is exactly what happened. The next morning his ship was in 10 or 12 great big pieces washed up on the beach. As I recall sixty-three bodies were found, his was not among them. They never found his body.

B. Did anyone survive?

A. Three of the crew members were the only survivors. The bosun and a couple of the youngsters on the crew were the only survivors. Everybody else, 133 drowned in the storm.

B. Were the women chained or in cells?

A. No, they were not restrained. Originally, as the scenario unfolded, they were put below in the prison space in the hold. But during the course of the storm, either the deck split, the poop broke up or the hatches burst because at the end, the women were out on the deck and washed over the side and drowned.

B. This is going to be a great book. It’s a story that, as I hear you tell it to me, I’m quite fascinated by. I know you said you have a deadline next year but what is the release date?

A. Well, it’s the same publisher and they typically take between ten and twelve months to go from when you deliver the manuscript to when the bound book comes out of the printer. And they really move pretty fast. That’s good time for the process that the manuscript goes through. My guess is that it will be in spring 2011; maybe late spring 2011; early summer…something like that. It often depends on the publisher. They publish about 70 to 80 books a year. It kind of depends on where in their schedule they’re going to put it.

B. That is one book I really look forward to reading Andy. Let’s move on to your most recent release, your third book which came out just last October 2008.

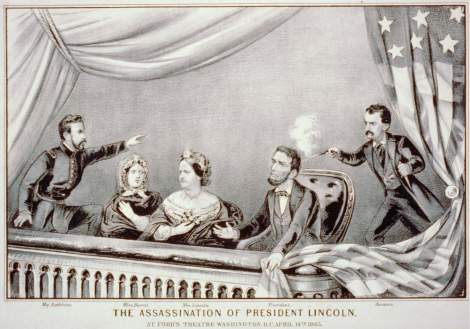

A. That’s the one we met over, so to speak, and is called “The Last Lincoln Conspirator: John Surratt’s Flight from the Gallows”. When I was researching my second book “Sailors in the Holy Land” I read in the biography of the American consul in Malta that in 1866 he attempted to arrest one of Lincoln’s conspirators passing through Valletta.

B. Really! (laughing).

A. And I said to myself “Now that’s crazy. How could that possibly happen?”

And I put that idea aside until I finished “Sailors in the Holy Land’. Then I came back to it to try to find out who was this Lincoln conspirator passing through Valletta in 1866. And it turns out it was true. It was young John Surratt, son of Mary Surratt, the woman who you know better than most, who was hanged for her part in the conspiracy. John’s story is the story of the last Lincoln conspirator. The title focuses on the fact that he was the last to be arrested, the last to be tried and last, by many decades, to die. He lived until 1916. He died in the arms of his family, his wife Mary Victorine Hunter, the second cousin to Francis Scott Key, the man who wrote the words to the American national anthem, and his children.

So it’s the story of Surratt’s flight through Canada, through England, across France to Italy where he joined the Papal Zouaves, the army of Pope Pius IX where he hid out for eleven months. He was discovered there and arrested. He escaped arrest, that’s the story anyway. The reality is he was freed by his jailors. Fled overland to Naples and got on a ship. Passed through Malta and here’s where William Winthrop tried to arrest him and got all the way to Alexandria, Egypt before he was caught.

In Alexandria, he was caught, jailed and a navy vessel was sent to pick him up. On November 26, 1866 United States Ship Swatara sails for Washington with Surratt in chains in the corner of the Captain’s cabin. He will spend six weeks chained while being brought back for trial. The book takes him through his trial, through the subsequent legal proceedings in ‘67 and ‘68. He is quite astonishingly freed in 1868 and after unsuccessful careers successively as a teacher and public speaker; he ends up being an auditor for a steam ship line in Baltimore called the Old Bay Line operating steam vessels from Baltimore to Richmond and Baltimore to Norfolk. He will spend more than 50 years as the auditor for that company dying just a few years before WWI begins.

It’s another one of these odd things that not many people know about and when they hear about it they tend to be disbelieving…the idea that he did all these things all by himself in his 20s. He spent a year in the Pope’s army. He was arrested in Egypt of all places.

B. Andy, Who actually arrested John Surratt? During those days, I’m not quite sure what the protocol was and whether or not they issued an international warrant for him.

A. Well, it’s better than that. Surratt as he traveled through Canada and Britain and Malta was under the protection of British law. And it was very unlikely that he would have been arrested and extradited by the Brits. But when he arrived in Egypt he no longer had that protection. Egypt was a part of the Ottoman Empire. And the Ottoman Empire and the United States, several decades before, signed a treaty that provided that American citizens in the Ottoman Empire were subject to American law as executed by American diplomatic officials in the country. So when he stepped off the ship in Alexandria, he was met by the American Consul in Alexandria, Charles Hale, who simply arrested him. Hale asked that the Egyptians jail him until he could be extradited; he could be shipped back to Washington. He put him in an Egyptian jail for three weeks which must have been a real experience in 1866. And then when Swatara showed up the day after Christmas ’66 they loaded him on board and shipped him out. So he had unwittingly exposed himself to American law.

B. Now I have read one of Surratt’s published speeches from when he was doing his public speaking tour discussing his version of the events that transpired around the time of the Lincoln kidnapping plot and subsequent assassination. He must have been a good speaker because he comes off as being very ‘believable’ regarding what he told his audience about his involvement, which he claimed was fairly minimal. And yet what I find interesting is that historians generally believe that John Surratt was John Wilkes Booth right-hand man. What are your thoughts on this?

A. Well this is a complicated question. The prosecution at his trial tried to make the case that he was in Washington on Easter weekend, 1865 and participated directly in the assassination of the President. Surratt’s defense was the he was in Elmira, New York that weekend casing the Union prison holding Confederate prisoners of war in preparation for a possible prison break. And during the course of the trial, there were witnesses swearing to both sides of that. But the jury who heard that voted 8 to 4 to acquit him. The prosecution did a very bad job presenting their case. The defense did a good job presenting their case. And the New York Times finally concluded that regardless of where the members of the jury came from, and there were seven Southerners and five from the North on the jury, regardless of where you came from you could not have concluded that the prosecution had made a persuasive case. And in fact they didn’t. I personally, for what that’s worth, don’t think Surratt was in Washington. He clearly was Booth’s right hand man. He was his chief recruiter. But he was not in Washington, not in Maryland after the last day of March. I think that Booth’s decision making coalesced, came together, during the first two weeks of April. Remember they had that failed kidnapping plot in the middle of March.

B. Yes.

A. At the end of March Surratt goes to Richmond as a courier and he will spend all of April on a courier mission. And he will not be in Washington when the assassination of the President happens, when the assault on the Secretary of State happens, when the bungled plot to kill the Vice President happens and when the planned attempt on General Grant’s life never transpires because Grant takes a train out of town that day. And he’s nowhere to be seen.

I think in that fact Surratt was deeply involved with Booth’s plotting with respect to the kidnapping. I think the case has never been proven that he was aware of Booth’s assassination intentions. And I think it is more probable than not, that he was, in fact, in Elmira, NY when the assassination happened. I would even go farther than that. I would probably say that he was in fact there. I found that witnesses that identified him as being there very persuasive and at least half the prosecution witnesses that said he was in Washington were clearly lying for whatever reason.

B. Was there a reason why the prosecution decided to take that approach?

A. Poor judgment!

B. I guess (laughing)!

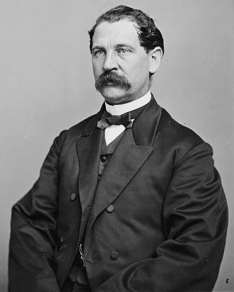

A. I think the prosecutor Carrington, the District Attorney, was just not a very smart man. He had the assistance of three other attorneys. The principal one was as civilian, Edwards Pierrepont, a New York attorney. And I think Pierrepont was a grandstanding, publicity hungry, a status conscious sort of guy who did just a very bad job putting the case together. Despite that fact, the judge George Fischer clearly believed in Surratt’s guilt and conducted the trial in such a way to make the prosecution’s case easier to present. He was so biased that even the newspapers were commenting on it. His charge to the jury for instance, at the end of that first trial, was outrageous.

Prosecutor Edwards Pierrepont

B. I guess that’s a good point. Were there not two trials of John Surratt?

A. No. There was one trial. The subsequent legal proceeding never went to trial. There were three indictments altogether. The first one went to trial. The second one the grand jury signed and sent forward. The third one the grand jury refused to sign. But there were a year’s worth of legal proceedings that did not rise to the level of a trial under a new judge, Andrew Wiley. And it was the last of those proceedings at which Wiley dismissed the proceeding and set Surratt free.

And that’s the story of the last Lincoln conspirator. Kind of a neat story, I guess as much as anything, because people have never focused on young John Surratt and his epic escape. There’s a mid-western newspaper at the time that said “Compared to Surratt’s escape, John Wilkes Booth’s twelve days was just a highway man’s ride”!

B. (laughing)

A. Well, I mean that’s silly because Booth was just the giant figure of all this. But in fact, he was only on the road for twelve days and Surratt almost for two years (chuckling).

B. What was your second book about Andy?

A. The second book was called “Sailors in the Holy Land”. And it is the true story of the American Expedition to the Dead Sea in 1848. Another one of these odd bits of history when you say to yourself “Well why would the US Navy have any interest at all in the Dead Sea in the middle of the 19th century”?

B. It is a question mark (chuckling).

A. When I first heard about it I didn’t believe that. So drawing on my navy experience I said “Of all the salt water on the earth that is the least likely place for the US Navy to operate” but I was wrong! In fact, the spring and early summer of 1848 there were sailors in uniform under the American flag, under arms exploring the River Jordan and the Dead Sea and quite unexpectedly all but one of them returned alive. It was a great success. It ended up answering some interesting scientific questions about the peculiar body of water. Everybody knew there were some odd things about the Dead Sea they just weren’t quite sure why and it was all caught up in Old Testament and religious imagery and everything else. But that book came out of a lot of reading I did and when I came across Mark Kurlanski’s book called ‘Salt’ a paragraph that said something about the navy’s expedition in the Dead Sea. I said to myself “Well, when I get time I’m going to look into that ‘because I don’t believe it”.

B. It’s funny how just one word, or phrase, will trigger you to start looking into something.

A. That’s not the story of the first book. “Adak”, the story of the ditching Alfa Foxtrot 586” off the Siberian coast in 1978, that’s a story I kind of grew up with. None of us who flew that airplane believed that you could survive putting it down in open water under the conditions that Jerry Grigsby did and live through it.

B. I guess we should give a quick summary of what your history was which related to this flight. You were a flyer in the US Navy?

A. I was. I got in the Navy right out of school in 1962. I started flight training immediately. Got my wings the day President Kennedy was assassinated in ’63. On that same day, he was in Dallas shot by Oswald, I was at Corpus Christi listening to all that on the radio at the Navy Exchange at Naval Air Station, Corpus Christi, Texas.

B. No kidding. Wow. You heard that live!

A. Oh yeah.I went to my first squadron. It was a P-3 squadron of Lockheed Turbo Props that the Navy used and was just buying. They were brand new airplanes for ocean surveillance, maritime patrol and anti-submarine warfare. I flew that airplane in three squadrons, on the East coast, the West coast and most places where there is salt water. There are places in the South Pacific and South Atlantic I didn’t get because the Soviets didn’t send their submarines there.

Lockheed P-3 often called the Orion

B. Was there a reason it had to be salt water?

A. Well we were looking for submarines.

B. Oh I see.

A. Anywhere there was salt water that the Soviet Navy operated submarines in, the Mediterranean, the North Atlantic, the North Pacific, the Western Pacific and the Indian Ocean. All those places we spent a fair amount of time working over making sure we knew where they were and what they were up to.

B. That was a pretty volatile time right around then too!

A. Well, it was an exciting time. The Soviets were building what was demonstrably the world’s biggest submarine fleet. Certainly the most threatening aspect of their naval force was that fleet. And we were working very hard, along with the Royal Navy and other friends and allies, to understand what they were doing, where they were doing it and how well they were doing what they tried to do.

I was fortunate that the ‘70s and ‘80s, we were very, very good at what we did. It was the golden age of air anti-sub warfare and I had a lot of fun with it. My last squadron was one which I commanded from California in Moffett Field in ’76 to ’78 and then returned to Moffett Field to command the air station in the early 1980s. In ’86 I retired. I tell people that I spent the next 15 years learning to be a capitalist. And it’s true. In the naval service you’re not dealing with making the payroll or selling the product or any of that. So for the next something years I did. And that worked out well enough that about ten years ago it became possible for me to write full time.

B. I understand that you worked in the Pentagon as well. When did that occur?

A. I worked in the Pentagon a number of times. It got to the point that I was going back and forth from the squadron to the Pentagon. At first I was on the staff of Chief of Naval Operations, both on his staff and personal staff. I next ended up on the staff of the Secretary of Defense, on his personal staff. And the last job was, again on the Navy staff in the Plans, Policy and Operations Office of the Navy Staff in the mid ‘80s. I may be one of the few people who enjoyed every assignment I had in the Pentagon. It’s traditional that people complain about it. I found it enormously interesting. I thought that the people I worked with were smart, dedicated and trying to do a good job and I thought it was a useful thing to do.

B. I want to get back to your first book, but mentioning the Pentagon, 9/11 comes to mind and I want to know what your feelings are on that and if you knew some folks in there.

A. No, that was far enough away from me. I’d worked in those offices. I knew the geography. I have a pretty good idea what it would have been like inside of that building at the time. By the time that happened, the people who were inside were a generation behind me. My sympathy, my horror and my unhappiness was generic rather than specific.

B. What years were you in the Pentagon?

A. The first Pentagon assignment was ’70 to about ’74 doing different jobs. I was back there during most of the Carter administration through the late ‘70s, early 80’s working for Secretary Brown. I was back there again ’85 and ’86 on the Navy Staff. Altogether about nine years or so! Seems like a long time in one building. But there were four different jobs, very different people and all of them I thought were worth doing.

Beyond that, I spent a year in Vietnam and a bunch of time flying airplanes. I did some time at school and some graduate work for a couple of years.

B. Were you in Washington in ’83 or had you already gone to California at that time?

A. No, I think I was already in California. I was at Moffett Field then for Moffett Field’s 50th Anniversary. The air station was built as a WPA project during the depression and its 50th anniversary we celebrated in ’83 with a spectacular 3-day weekend and air show and carried on vitally. So I remember that date pretty clearly. I still have two bottles of wine in the house with labels from Mirasou Vineyards celebrating Moffett Fields 50th anniversary. My guess is that stuff would just taste awful.

B. There’s probably some serious vinegar in there (laughing).

A. I think it could peel paint (laughing).

B. (laughing)

A. But the bottles are beautiful and it’s a nice memory.

B. That’s terrific. What was the plane that you flew that related to the Adak story?

A. It was the same airplane, the Lockheed P-3. It’s really called the Orion. It was a four engine, land based turboprop, 127,000 lbs when we started and ended up being about 132,000 pound airplane with four turboprop engines altogether about 17,000 horsepower. Just a great airplane! Full of expensive equipment and normally carrying a crew of between ten and twelve.

B. Now you had mentioned before that this plane was not meant to float.

A. Yeah, think for a moment. This is not a seaplane. This was originally an airliner. It’s designed for pressurized cruising at altitude. It doesn’t have a keel; it doesn’t have any of the kinds of things that make a seaplane into a seaplane. And it’s what makes the landing of the US Air aircraft in the Hudson River so stunning. The idea that he could that and survive it and get everybody out…I mean that’s an authentic miracle.

B. I understand. Wow.

A. For the same reason when Lieutenant Commander Jerry Grigsby in end of October, ’78 put his airplane down into the open Pacific in thirty foot seas, the idea that it would hold together at all, long enough for people to get out of it, is just amazing. It took extraordinary skill and frankly a fair amount of good luck too.

B. How long was that plane in the water?

A. It sank in about two minutes. The survivors’ stories vary between two to four minutes. Your sense of time is really skewed under those kinds of stresses. But they hit the water, broke up just behind the cockpit and just in front of the tail and sank very quickly. Before it went down, 14 of the 15 men aboard had time to get out. And 13 out of those 14 managed to get into a raft. Tragically, the pilot Jerry Grigsby did not. He got into the water, he was swimming towards the raft but he was never able to catch it. Under the wind and the waves at the time there was nothing the guys in the raft could do. And Jerry drifted off to sea and he was lost at sea.

B. This was a storm that took the plane down?

A. That part of the North Pacific around the Aleutians has some of the nastiest flying weather or for that matter steaming weather in the world. It’s very very tough because that very cold dry air comes off of Siberia and hits the relatively warm moist air of the Bering Sea and it just spins up storms that are just ferocious. Those storms come tracking down through the Gulf of Alaska and tear up the North Pacific and Jerry had the misfortune of being operating right on edge of that such that when he went to put Alfa Foxtrot 586 down in the water he was facing 25-30 foot seas.

B. Now he put it down for what reasons?

A. He had a problem with the No. 1 propeller. It translated itself into four separate engine fires. The first two engine fires he could put out. The aircraft has fire extinguisher systems that will put out two fires on any one side. The third fire blew out. When the fourth one flared up, he realized that he was out of options, a little bit like the captain of Amphitrite. He’d run out of options and had to do something decisive and what Jerry did was, before the wing burned off and killed them all, he put the plane into the water. And everything flowed from there.

B. Did this happen right when the storm hit?

A. No. There had been a storm out there the whole time. They were going out from Adak for a flight that was scheduled to be 9 hours. That weather was there and stayed in the Aleutians for the next couple of days. As a matter a fact while the search and rescue flights were being flown looking for them the weather moved down the Aleutian chain, from west to east, and progressively closed the Air Force base and the Navy bases and things like that, tremendously complicating the conduct of the search and rescue missions.

B. Although Jerry Grigsby didn’t make it, how many men were in the life raft at this point?

A. There are now thirteen in the raft at about two or three o’clock Thursday afternoon. Thirteen of them have made it into two rafts. There are nine guys in a seven-man raft and four men in a twelve-man raft.

B. Are they lashed together?

A. The rafts blow apart. After just a few minutes they blow a couple of miles apart and they don’t see each other. Over the course of the next twelve hours three of the young men in the nine-man raft die of exposure. And it’s pretty clear that the rest of them had just a few hours to live. Meanwhile, there is a frantic effort to rescue them. And that effort includes an appeal from Washington to Moscow for assistance because there are no American flag vessels or US Navy ships in the North Pacific around them. It turns out there is a Soviet fishing trawler, the Mys SInyavin. Mys SInyavin is directed by the Soviet Fisheries Ministry to turn around and sail to the wreck site. And she is led to the rafts by a US Coast Guard airplane that has been flying on top of the rafts.

B. Oh, so they know where they are?

A. They know exactly where they were. They just can’t get them out of the water. And the water is going to kill them. The nearest Coast Guard cutter is 2-1/2 days away. It’s a Coast Guard cutter, also out of Adak, Alaska, Hamilton class cutter, and she’s not going to get there until Saturday morning. This is now Thursday night. So the Mys SInyavin turns around, heads back to the wreck site and manages in the middle of the night to collect the ten living men, who are hours from death at most, and the three bodies. They will spend a week in the Soviet Union in two hospitals, one in Kamchatka, the Kamchatka Peninsula and one on the Soviet mainland. And then quite remarkably and quite surprisingly they are released. And they are home Saturday, nine days after they hit the water with the three bodies of the young crewmembers who died. So the story is about a ten day story. What makes it exciting is that the sources on that were very very good. I have in fact, among other things, the tape recordings of the emergency radio transmissions between the aircraft and the ground in 1978. And when you listen to them it is breathtaking. One of the young crewmembers, the tactical coordinator, is talking to Elmendorf radio and at 200 feet above the water, he is telling Elmendorf that, okay, they are going in. They’ve stretched this out as long as they can. He’s sitting at a window. His station has a window. He’s sitting above the water, looking at these horrific waves, the horrific wind, telling them that they have 15 of them aboard, that they’ve got life rafts, that they’re all wearing survival suits. And his voice is so calm and so collected that he sounds like a sports announcer watching a ballgame. You would think that there would be something in his voice that would tell you he thinks he was going die because he had every reason to believe he was. And it’s not. The kid’s just out of college. It’s just an extraordinary demonstration of professionalism and coolness that, every time I hear that transmission, and I’ve probably heard it 150 times, I marvel at it.

B. I assume that when you do a book tour you play that tape during your talk. It must be breathtaking for folks who hear that.

A. I play that tape and play a number of sections from it. I begin with that because it’s just so arresting to hear that. And then I explain to people “Okay, this is what you heard. Now let’s listen to it again”. And as I say, every time I go through that I get a lump in my throat. Matt Gibbons is the guy whose voice that is. Matt lives on Half Moon Bay in California now. He works for a technology company called Novellus. You look at Matt today, he looks like…do you know the American cartoon character Elmer Fudd?

B. Yes (laughing).

A. Okay. Matt looks a little like Elmer Fudd. And what you don’t realize looking at Matt is here’s a guy of exquisite courage. I mean just extraordinary courage. And it’s all wrapped up in this quite ordinary body. Interestingly enough, I mentioned to you that Jerry Grigsby died. He was never able to swim to a raft. Two years later, Matt married Jerry’s widow. They live today, happily, more than thirty years later, in California where this is still a big part of their lives, this whole memory.

B. Have you met most or all of the survivors?

A. All of them. With one exception they all cooperated very generously while I was writing the book. One of them was in my squadron for a brief period of time. The navigator was in my squadron before he went to this squadron. And the guy who wrote the Navy investigation for this I knew. The commanding officer of the squadron was a contemporary of mine so I knew him too. So it was a story in the family and it was possible to tell it especially persuasively, especially convincingly because I had flown the airplane most of my life. I’d operated out of that part of Alaska. I had flown off the Soviet coast where they were flying. And I kind of understood a lot of what was going on there although I won’t pretend to you that I have any experienced anything remotely like what they went through which is just an extraordinary event.

B. That’s pretty amazing.

A. It’s a neat story.

B. And you’ve picked four rather amazing stories. I can’t wait to see what’s up your sleeve next, Andy.

A. I haven’t even begun to think about it. I’m deep in Amphitrite and her women. What I try to do is to always be working on a book and in the intervals around the edges of that, I generally write a periodical article each year. There has been one published in Naval History Magazine every year for the last, I don’t know how long. And they’re generally 5000-6000 word features on exciting adventures. The American expedition up the Congo [B. Note: This article was voted Feature of the Year by Naval History magazine in 2006]. The American expedition down the Amazon. Henry Eckford, an American ship designer in the 1830s, who ended up quite improbably running the shipyard for the Ottoman sultan in Istanbul. They’re stories that are odd and they’re interesting and it gives me a chance to take a midway break from working on the book to dip into something else for a couple of weeks and then refresh and revitalize until I get back into it.

B. When you retired from the Navy, what rank were you at?

A. I was a Captain.

B. And you also spent some time in Vietnam?

A. I spent a year in Vietnam on the MACV staff at Ton Son Nhut. My graduate degree was in Southeast Asian Politics. I’m a graduate of the School of International Affairs, because I expected to go to Vietnam, I concentrated on Southeast Asia.

So when I finished the degree program, as expected I ended up going to Vietnam and I spent a year in Psychological Operations. It was our mission to persuade the members of the North Vietnamese Army in the Republic of Vietnam to surrender and to persuade the members of the Viet Cong to rally to the government. And you can tell by the way the war came out how successful I was in that. Which is to say, not at all!

B. (laughing)

A. And I spent many years reflecting on that failure. And I finally concluded that you can’t get people to quit if they think they’re winning. And there is no reason why they thought that they weren’t winning, because they were. It was clear to them, and consequently all our persuasion, all our dropping of leaflets on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, all our propaganda broadcasts, one thing and another we were doing. We were just going through the motions. We were having no effect whatsoever.

B. At the time, did you know that?

A. At the time, I suspected it but I didn’t know it, and I wasn’t going to quit trying. As you can tell, I’ve had a lot of time to think about it. And it was very ill conceived, the effort we made. And we used to drop 12 or 13 million propaganda leaflets at a time. There must be parts of Laos today that you can still walk hip deep through propaganda leaflets assuming that they haven’t disintegrated into paper mache. And that effort was just silliness.

B. But at the time, it seemed to make sense (laughing)!

A. Well (laughing) Lord knows we were trying! One of the things we tried to do is we decided that people were not picking up leaflets because they’d get in trouble if they did.

B. Oh, okay.

A. So people said, “What would they pick up. They’d pick up money, wouldn’t they”? So there was a program where one side of the leaflet was printed with money. Printed as if it were a piaster or a North Vietnamese dong or something. So then we realized “Hey, that’s really dangerous”! You start that stuff then you encourage people to counterfeit your money and now all kinds of stuff unravel. So, we went from that to the idea of “Why don’t we print propaganda on tobacco leaves!”, because all these guys will pick up tobacco to make cigarettes to smoke. But you start trying to feed tobacco leaves through high speed printing presses…

B. (laughing loudly).

A. I want to tell you the mess you can make is just stupefying! Modern equipment or what was modern then, can’t handle something like that. So there are a lot of things we did that, that when I look back on, I say to myself “Gee that was silly!” But there are more important criticisms than what I’m saying.

B. These are the stories that the general public never hears (laughing). I don’t think they’re stories out of school. They’re just things that happened.

A. We set up a propaganda radio station in the Highlands of Pleiku and people started saying “Hey, wait a minute. Who’s going to hear this? There aren’t enough radios around.” So the decision was “Alright, let’s buy some really cheap radios, fix tuned to this station and just air drop them.” And then there was decision made that said “Okay, we have to make sure that there is no way that these radios can be traced back to us.” So a some expense, we had a bunch of radios made (little things about the size of a pack of cigarettes), we had a bunch of these things made and paid quite a bit of money to make sure that there was no component in the radio that identified its origin. You know, Made in…made here, or made there. And then we started scattering these things up and down Vietnam. Well, unless you believed in the Radio Fairy, there’s only one place these things could have come from…

B. (laughing)

A. …the United States! So the whole concept of dropping these mysterious radios that nobody knew where they came from was silly because everybody knew where they came from.

B. Considering the channel that they were locked in on…

A. There was one player in that part of the world with enough money to do that…

B. & A. (laughing).

A. Anyhow, I’ve had a lot of time to think back on this stuff. It was odd. Very odd. And more than odd it was in many respects, tragic.

I felt very strongly as a young man. One of the parts of the deal was if you were a commissioned officer in regular Navy, if there was a war going on you were honor bound to serve. And on the strength of that I’ve never regretted what I did but I have looked back with a certain amount of bemusement as to just how it all came out.

I hope that gives you a sense of maritime adventures that I’ve been working on and writing up and how it is I got from the rescue of Alfa Foxtrot 586 to the trials and tribulations of John Harrison Surratt Jr. and finally to what tragically happened to the women aboard the convict transport Amphitrite off the beach of Bologne in 1833.

B. This has been fascinating history and I’m really thrilled that you shared it with us. It has been my pleasure to talk with you and share these great stories with my readers. Andy, thank you so much.

A. I’ve enjoyed meeting you over the ether. I’ve enjoyed talking to you and I appreciate your interest and attention.

B. Thank you.

END

—————————————————————-

I want to thank Andy for this interview and look forward to our continued conversations in the future.

Best

Barry

outreach@awesometalks.com

Julia Gardiner Tyler, 2nd wife of President John Tyler and 1st lady of the United States (1844-45). Born May 4, 1820. Age 192.

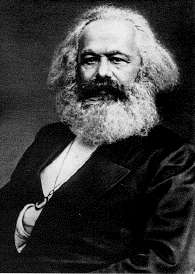

Julia Gardiner Tyler, 2nd wife of President John Tyler and 1st lady of the United States (1844-45). Born May 4, 1820. Age 192. Karl Marx, Communist philosopher. Born May 5, 1818. Age 194.

Karl Marx, Communist philosopher. Born May 5, 1818. Age 194. Julia Ward Howe, writer of ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’ which was first published 1862. Born May 27, 1819. Age 193.

Julia Ward Howe, writer of ‘The Battle Hymn of the Republic’ which was first published 1862. Born May 27, 1819. Age 193. Peter Il’yich Tchaikovsky, Russian Composer. Born May 7, 1840. Age 172.

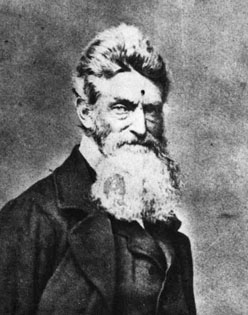

Peter Il’yich Tchaikovsky, Russian Composer. Born May 7, 1840. Age 172. John Brown, abolitionist who led attack on Harper’s Ferry. Hanged in 1859. Born May, 9, 1800. Age 212.

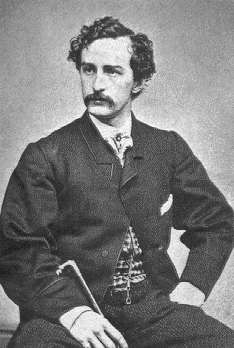

John Brown, abolitionist who led attack on Harper’s Ferry. Hanged in 1859. Born May, 9, 1800. Age 212. John Wilkes Booth, assassin of President Abraham Lincoln. He witnessed John Browns hanging in 1859. Born May 10, 1838. Age 174.

John Wilkes Booth, assassin of President Abraham Lincoln. He witnessed John Browns hanging in 1859. Born May 10, 1838. Age 174. Florence Nightingale, Italian nurse. May 12, 1820. Age 192.

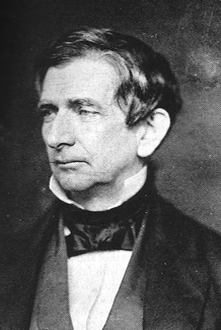

Florence Nightingale, Italian nurse. May 12, 1820. Age 192. William Henry Seward, Secretary of State (1861-69). Born May 16, 1801. Age 211.

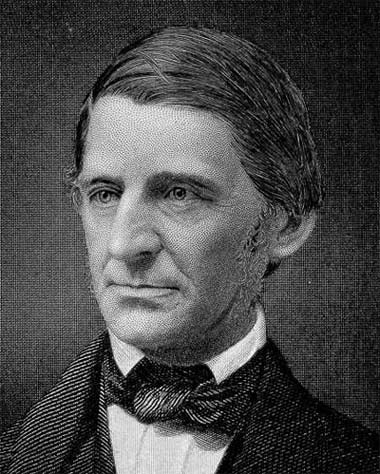

William Henry Seward, Secretary of State (1861-69). Born May 16, 1801. Age 211. Ralph Waldo Emerson, US writer. Born May 25, 1803. Age 209.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, US writer. Born May 25, 1803. Age 209. James Butler ‘Wild Bill’ Hickok, American cowboy and scout. Born May 27, 1837. Age 175.

James Butler ‘Wild Bill’ Hickok, American cowboy and scout. Born May 27, 1837. Age 175. Walt Whitman, US Poet. Born May 31, 1819. Age 193.

Walt Whitman, US Poet. Born May 31, 1819. Age 193.

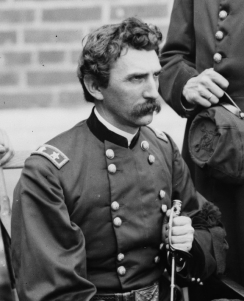

Brevet Major General John Hartranft – Read the Order of Execution on the scaffold to the four condemned Lincoln conspirators. He later became Governor of Pennsylvania from 1872 to 1879. Born December 16, 1830. Age 182.

Brevet Major General John Hartranft – Read the Order of Execution on the scaffold to the four condemned Lincoln conspirators. He later became Governor of Pennsylvania from 1872 to 1879. Born December 16, 1830. Age 182.